- Home

- Jimmy Connors

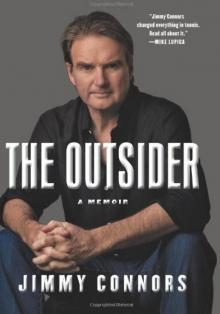

The Outsider: A Memoir Page 4

The Outsider: A Memoir Read online

Page 4

The kids used to give me a hard time, constantly teasing and pushing me around, especially after the monsignor let me leave school early in the third grade to go play at Jones Park. Johnny looked out for me as much as he could. He was good with his fists and protected me because I was small for my age.

Even when Johnny wasn’t around to help, I didn’t care how the kids at school treated me. I figured I’d be leaving East St. Louis, anyway. Mom had told me tennis was my way out of there, so I put up with the bullying and got on with it.

In class, I was a clock-watcher. I’d look at it every three minutes and the day would just drag on. My attention span was nonexistent, and it was an effort for me to read. I’d read lines multiple times because I’d lose my place or keep reading the same lines over and over again. Then I would forget what I was reading and have to start all over. Like I still do today.

It wasn’t until I was an adult that I discovered I had something called an ocular-motor sensory deficit. That’s the new, twenty-first-century version of you can’t read. My eyesight was good, but my eyes didn’t have the ability to work together. If I could have read with just one eye, I probably would have done OK, but I couldn’t track the words using the two of them. No wonder I also had a short attention span and had trouble with reading comprehension.

Looking back, I have no idea how I was able to play tennis at all, but on the court I had perfect vision. I was able to see the ball quickly when it came off my opponent’s racquet and track it into my hitting zone, trying to keep my eye on the ball until I made contact. Not bad for a guy who couldn’t follow words on a printed page.

This eye problem was the reason why I always insisted on three-paragraph contracts in business. You tell me what you want me to do, I’ll do it, and you’ll pay me. I couldn’t read 20 pages of a contract. I had no interest in the small print.

It wasn’t until I turned 45 and got reading glasses that I was able to see clearly. It only took 30 years. On a flight from California to New York, my wife, Patti, will finish an entire book while I can read only about 60 pages. When I play tennis these days, I don’t wear my glasses; it’s too uncomfortable, because I wear progressive lenses. It’s better for me to see the ball come off my opponent’s racquet, because I have a feel for where it’s going. Once it crosses the net, I lose sight of it, so that by the time the ball gets close to me, it’s a blur. Basically, I make my contact with the ball by memory. After playing for so many years, it’s funny how that works.

So all you guys on the Senior Tour didn’t know you were playing Mr. Magoo, did you? Funny what you’ll do to keep playing a game you love.

In many ways, I guess we were a pretty regular 1950s American family in those early days. I say pretty regular because some interesting characters used to visit our house from time to time.

My dad’s father, John T. Connors, passed away before I was born, and I’m sorry I never got to know him. My brother was named for him. John T. had been the police commissioner before he was elected mayor. There was a lot going on in City Hall during those years. Because of its river, railroad, and stockyards, East St. Louis was closely connected to Chicago. Back in 1947, Grandpa Connors was among 19 officials indicted for malfeasance for ignoring evidence of gambling and election irregularities. For my grandfather to have survived as mayor for as long as he did, he must have been strong-willed and one hell of a mover and a shaker. I sometimes wondered how many of his character traits I ended up inheriting. As time went on, I discovered more than a few.

One of my grandfather’s friends, who was also close to my parents, was Frank “Buster” Wortman. Buster owned the Paddock lounge, in East St. Louis, where our family would go for dinner on occasion. One night, when Johnny and I were about eight and six years old, respectively, we were in the restaurant when a group of men burst through the front door. They looked around, rushed over to a corner of the room, and started shooting at four guys who were halfway out of their seats. A bunch of Buster’s men surrounded our table and rushed us all into the kitchen. It turns out that Buster was the target and the shooters got the wrong table. I don’t remember seeing him much after that. It was only years later that I found out that Buster had been a bootlegger, a gambler, and a member of the Shelton Brothers Gang during Prohibition. He then went on to take over St. Louis’s illegal gambling operations in Southwest Illinois.

After my dad got out of the service, as a favor to my grandfather, Mayor John T., Buster offered to let my dad open up all the gambling for him in Granite City, a steel town near our home. Dad started doing that, but then Grandma Connors found out and put a stop to it. That was when Dad became the general manager of the Veterans Bridge, where he pulled in $10,000 a year. Talk about a life-changing decision.

But not every character from Mayor John T.’s interesting past got us caught up in the middle of a gunfight. One night, right around Christmas in the early 1980s, I had just come back to visit my family in Belleville after a full year on the road playing tennis. We decided to go meet Johnny at Charlie Gitto’s Italian Restaurant, in downtown St. Louis. The owner, Charlie, had been at Johnny’s wedding, and he was glad to see Mom and me and made a fuss whenever we’d come in for dinner. Two of Charlie’s more colorful friends, Ralph “Shorty” Caleca, and his driver, Joe, were in the restaurant, and Johnny invited them to join us for dinner. Shorty had been one of the top bosses of organized crime in St. Louis in the 1940s, and he still held a great deal of power.

Let me back up for a second. From the time Johnny and I were little kids, Mom would sing a jingle to Dad just before the holidays: “All I want for Christmas is a gray cashmere sweater with a white fox collar.” We’d hear it every year, and the joke was that she never got the sweater. For some reason, that night at dinner, we got to talking about that jingle. Shorty, who was in his late seventies at the time, suddenly growled:

“What’d she say? What’d she want?”

Johnny gets a call the next day from Charlie saying that Shorty wants to see him. So Johnny goes to the restaurant and there’s a box with Mom’s name on it.

“This is from Shorty. He says Merry Christmas to your Mom,” says Charlie.

Johnny brings the box home and we put it under the Christmas tree. The next morning, Mom opens the box and I think you can guess what was in it.

I played my first junior event when I was seven years old. Mom drove Johnny and me a hundred miles to Flora for the Southern Illinois tournament. It was my first real tennis competition that was part of a circuit, and it was a big deal for me. Johnny won the event, and I was happy for him. I saw what it was like to walk off with the trophy.

I always looked up to Johnny, and it was right around this time that he started becoming interested in other things besides tennis. We would be practicing, and Johnny’s shots would suddenly go flying over the back fence. Mom knew he wanted to be somewhere else, and she let him go. I wasn’t like that. If I was on the court, I was there for the duration, trying to do the right thing.

The following year, Mom and I went back to Flora and I won my first-ever competition. I’d spent the year playing small events around the district, gaining experience and learning what it took to win. Johnny didn’t go with us, because by that time he was a confident ten-year-old helping Dad out at the Veterans Bridge tollbooth. He worked on the bridge through high school and always seemed to come home with a pocket full of dimes and quarters. He had a knack for that.

As we got older, Mom could see we needed more than just the backyard or Jones Park to hit balls or play doubles against other kids. However, finding a better place for us proved to be a challenge.

The Knights of Columbus building on State Street, East St. Louis, was a Catholic social club that had a small basketball court behind a huge set of wooden doors that were locked but not very secure. There was a gap at the bottom of the doors that was just large enough for Johnny, Two-Mom, Mom, and me to squeeze through on our stomachs. There we could practice, uninterrupted, against the wall and on the

hard wooden floor. After we finished, we’d play basketball with Mom and Two-Mom.

It was at the Knights of Columbus basketball court that I began to refine a technique that Mom had been drilling into both Johnny and me from our very first lessons in the backyard: hitting the ball flat and early. On those floorboards, if you didn’t attack the ball, it would fly past you before you had time to set yourself. I sometimes wonder if Mom was aware of the progression from the backyard court to Jones Park to the Knights of Columbus and then on to the armory. Had Mom planned it or was she just seizing opportunities as they came her way?

Mom first took us to the National Guard armory in 1963, and I couldn’t believe how big the place was. Its heavy steel doors looked large enough to drive a tank through. Above the doors was the military crest with words carved into the stonework: ARMORY, 138TH INFANTRY, MISSOURI NATIONAL GUARD.

Inside the armory’s huge gymnasium, tennis courts were marked out on the highly polished floorboards. The armory was the only indoor tennis facility in St. Louis, and I was from the wrong side of the Mississippi River. Finding a game was hard, I was small, my mother was my coach, and I wasn’t a member of the clique of kids from the good side of the river. In their eyes, I was an outsider, taking up valuable court time. But Mom figured out a way to make them accept us. She offered to coach some of the kids if they would hit with me. I would hang around all day on weekends and during vacations, if there was a latecomer or a no-show, I’d be out there like a shot, offering to play with anyone. That sense of being an outsider has never left me.

If I laid the foundation of my game at the Knights of Columbus, I took it to a new level at the armory. Balls came off that surface like lightning and would be gone before you knew it. There was no time to stay back and let the ball come to you. You had to move to the ball, meet it on the rise, and attack it. The three years I played at the armory set me apart from a lot of the other players of my generation. Many of them, like Borg, sat back, waiting for a mistake. I took the game to them, looking to be the aggressor.

For the first few months we played at the armory, Johnny would come with us, but he soon lost interest. After Mom and I finished practice, I would go look for my brother. I usually found him climbing all around the armory roof trying to hit passing cars with the crab apples that grew from the trees near the entrance. That was on his good days.

One day I couldn’t find Johnny anywhere, so I sat on the steps of the armory and waited for Mom to finish coaching the other kids. I heard Johnny calling my name and looked over at the compound for military vehicles. Johnny was sitting behind the wheel of an Army jeep, driving in a circle.

“Come on, Jimmy, I opened the gate. Jump in.”

When and where had Johnny learned to pick locks and hotwire cars? I still haven’t figured that out. I ran through the gate and jumped into the jeep with Johnny. The tanks and armored vehicles parked in rows made for a perfect racetrack.

“You do know how to stop this thing, right?”

“No idea,” Johnny replied.

It was at that point that Johnny slammed the jeep into a big green truck.

“Let’s get out of here,” said Johnny. “We don’t want to get court-martialed.”

Johnny and I loved watching westerns on TV and playing cowboys and Indians with our friends. One night, when I was 11, we were lying in bed talking about how great it would be to be out there riding the range like the real thing.

“Let’s get a horse!” Johnny said.

“Yeah, OK,” I said. If Johnny thought it was a good idea, then so did I.

Growing up, I’d have given my left nut to be part of whatever he was doing. I loved tennis, but when I came home after practice I just wanted to hang around with my brother. He was always good about that, but in later years, when he was involved in riskier activities, he became protective of me and wouldn’t let me tag along. And thank goodness for that.

We told Dad we wanted a horse and he thought we were crazy.

“OK, you want a horse, you buy it yourselves.”

Buy it ourselves? Horses and boarding cost real money. But then Johnny had his stash from collecting tolls on the bridge, and with it we bought a riding quarter horse. Johnny paid my half, and my down payment was cleaning out the stall the first few weeks. Dad soon began to share our interest in riding and eventually bought his own horse, as well as one for me, a two-year-old palomino named Peaches. Boy, was she a handful, and I went flying over her pretty head countless times.

We used to jump a train that led to a low trestle bridge spanning a creek by our home and take the horses along the levee and into the hills to look for arrowheads. There, we would make corrals for the horses from fallen trees and camp out overnight. It was a lot of fun, but making believe we were living in the days of the Old West turned out not to be my thing; I liked the comforts of home—no furry creatures in my bed, thank you.

Within the year, Dad sank his own money into the stables we used, and it turned into a business. At one time we had about 50 quarter horses there, with bloodlines, starting gates, and roping.

Right around the time that Johnny bought his horse and started working with Dad on the Veterans Bridge, Mom knew that Johnny wasn’t going to dedicate himself to tennis. She basically told him to go ahead and do what he thought was right. The implication was: “I’m going to devote myself to Jimmy now.”

Most of my summers were spent traveling with Mom. On the junior circuit, you advanced in stages, gaining experience and confidence along the way. First you played a local district tournament, then a USTA section, and if you were good enough, you went on to the nationals. I began to play the Missouri Valley Section events of the US Tennis Association tournaments, which covered Illinois, Kansas, Missouri, and Iowa. As I improved, I would come home between tournaments for only a day or two before leaving again.

In 1963 I made the first of four visits with Mom and Two-Mom to the Manker Patten Tennis Club, in Chattanooga, Tennessee, for the national championships—first for boys 12 and under, then 14 and under. I didn’t win any of them. I made the quarters on the first trip and the semis a year later, where I was beaten by Brian Gottfried, who would end up becoming a friend and competitor throughout my career on the professional circuit.

My junior record was good enough to qualify for the tournaments I wanted to enter, but it wasn’t spectacular. By the end of my junior career, I made the US top ten for my age group, but I was far from being the best. Gottfried, Dick Stockton, and Eddie Dibbs were considered better than me, and they were.

Mom’s biggest challenge with me during my junior years was trying to rein me in. I hated losing. I wanted to practice more, to play more, to travel more so that I could start winning, and when I couldn’t do that I would become discouraged and frustrated. But Mom always seemed to figure out a way to lift my spirits.

“Don’t worry, Jimmy, you’re just not big enough yet. That’s the only reason you aren’t winning. It’s going to happen, trust me. Keep working hard, do the right things, and the wins will follow.”

When I was on the junior circuit Mom knew that winning or losing was just one part of the process. She wanted to see me improve, to lock in new shots, and to move better. Rushing things didn’t make sense to her. She always looked at the big picture. But what was the big picture? There was no money in tennis, so my career beyond the juniors was important only in that it could lead to a tennis scholarship to a top university and allow me to experience life beyond East St. Louis.

When I first traveled to the tournaments where I had to sleep overnight, I stayed in a room with a few of my tennis buddies. Someone always had to sack out on the floor—usually me. Early on in my junior career I told Mom that living like that was just not my thing, and she arranged different accommodations away from everyone else. You can guess how that’s been interpreted over the years.

Gloria Connors drove a wedge between her son and his peers.

Gloria Connors thought her son was better than everyone

else of his generation.

Gloria Connors refused to let her son become friends with the other boys.

Gloria Connors forced her son to view other kids as the enemy.

Bullshit. I separated myself because I wanted to and because I hated feeling crowded. I wanted to concentrate on my tennis. This wasn’t a vacation for me. It was a time to play the best I could. That’s all I cared about.

We’re in Miami at the Orange Bowl in 1964, walking by the practice courts. A small crowd is watching a couple of guys practicing on the court nearby, and Mom and I go over to see what’s happening. I hear this weird noise as the ball flies off the strings of a racquet. It’s not the normal sound I’m used to and it gets my attention. The racquet the guy is holding is silver, with two prongs at the top of the handle. Even the head looks different. It turns out to be a demonstration by Wilson Sporting Goods of a new prototype racquet they’re calling the T2000. It’s cool, and I really want one. Mom happens to know the Wilson rep, Jack Staton, who is running the event, and she asks him if we can get a T2000. He tells her it’s a one-off but says he’ll see what he can do.

A few weeks later, a package comes to the house addressed to me. Inside, wrapped in plastic, are four T2000 racquets and a note: “Jimmy, let me know what you think. Enjoy the racquets. Jack, the Wilson Tennis Company.”

The racquets were sent unstrung. Two-Mom looks at them and makes a face. “There aren’t any holes. I don’t see how to string that thing.”

Pop picks up one of the racquets and turns it over in his hands. “I don’t know, either, but we’ll figure it out.”

For an hour they hunch over the kitchen table with a pick and awl. Instead of pushing the strings through holes and tying them off, with the T2000 you have to weave them in and out of the frame.

The Outsider: A Memoir

The Outsider: A Memoir