- Home

- Jimmy Connors

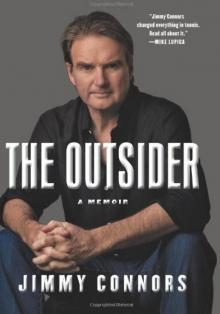

The Outsider: A Memoir Page 6

The Outsider: A Memoir Read online

Page 6

Pancho and I had a good relationship from the very beginning.

“All I ask,” Pancho said, “is that you believe in yourself. No negative thoughts, no excuses. Lose like a man and win like a man. If you’re injured, don’t play; if you play, you’re not injured. Always give one hundred percent and I’ll be happy.”

Those words stuck with me throughout my career.

Mom had handed me over to Pancho so that he could take me to the next level of competition. The only thing she told him was “Leave Jimmy’s game alone. I don’t want you to change that. You provide whatever else is necessary.”

Pancho was no angel. He helped me to gain experience off the court as well as on it, and that was just as important to him as the tennis. He took Spencer and me out to restaurants and taught us that having a drink with dinner was no big deal. He showed us how to handle ourselves early on, at 16 years old. If you think that’s all he taught us, well, use your imagination.

Pancho kept on top of my schoolwork, too. If Spencer and I missed class or walked on the court too tired to take care of business, then we answered to Pancho, a no-nonsense guy even down to the smallest detail. One day Spencer and I decided that our buzz-cut haircuts were out of style and it was time to make a change, so we told the barber to let the rest of our hair grow as long as the tuft in front. Afterward we went to the tennis club to hit a few balls, and Pancho walked straight onto the court.

“I thought you guys were going to get your hair cut,” he said.

“Yeah, we did. It’s the new look.”

We were soon on our way back to the barber. The buzz cut was suddenly back in style.

We had more freedom on weekends. On Friday nights, Pancho would ask us if we had practiced our tennis and we’d say yes. He would ask us if we had done our homework and I’d say, “Why would we want to do that?” Even though that was my attitude toward school, it wasn’t Spencer’s. He went on to graduate college and to become a successful lawyer, so school was an important part of his life. But on Friday nights, even Pancho would relax a bit and tell us it was time to go out and have some fun. And we did.

The Beverly Hills Tennis Club had been founded by Fred Perry and Ellsworth Vines, along with Golden Age movie star Fredric March, and it was only two minutes from Rodeo Drive. It was like a Hollywood club, and all the big names would be there, taking lessons from Pancho and other pros, playing on one of the five courts or just socializing. Burt Bacharach, Anthony Newley, Kirk Douglas, Julie Andrews, Lloyd Bridges, and countless other celebrities were attracted by Pancho’s personality and reputation. He even did a little matchmaking by introducing a girl he knew, Candy, to Aaron Spelling; they ended up married for almost 40 years, until his death.

Baseball legend Hank Greenberg was another regular at the club, and we played a few matches together. He was in his late fifties, so I played right-handed. It seemed only fair. Hank had been a first baseman for the Detroit Tigers in the 1930s and ’40s and one of the premier sluggers of his generation, smashing 58 home runs in 1938. One time I asked him what was so difficult about being a power hitter, and he said, “You have a round ball, you’re trying to hit it with a round bat, and you’re trying to hit it square. Nothing like finding the sweet spot.” When I wasn’t working on my tennis, I loved hanging around Mr. Greenberg, hearing his stories and gambling on backgammon.

Spencer and I were good friends with Desi Arnaz Jr. and Dino Martin Jr., Dean Martin’s son. When I first met Dino Jr., he was already a rock star and regularly on the cover of teen magazines, but what he really wanted to be was a top tennis player. He took lessons from Pancho and was naturally athletic, but he had just come to the game a little too late to excel. Spencer and I spent a lot of time with Dino, up at his father’s house, where there was a tennis court, and also in nightclubs where all Dino had to do was wink and through the doors we went.

I remember watching Spencer and Dino from the bar that overlooked the court at the Martins’ palatial home on Mountain Drive, in Beverly Hills, waiting my turn to play. All of a sudden, Dino’s father, the great Dean Martin, came up to me and introduced himself, all laid back and smooth, as he was in those Rat Pack movies. He asked me if I wanted a drink. Did he know I was only 16? I looked at him in amazement—a man I’d seen only on TV—and thought, sure, what the hell.

All of the TV and movie stars wanted to hit with the best young tennis players around, and they respected our ability on the court. Spencer and I decided maybe we could make a few bucks while we were at it. We’d play doubles for $20 a set, which was our gas money for the week. We gave our opponents a 4-0 lead, just to be fair. Talk about pressure. But I’ll tell you what—you don’t lose a match like that when you’ve only got $5 in your pocket. Pretty soon we began to win a bit too often, so we mixed it up a little, me playing with the weaker celebrity against Spencer and the better guy.

Bob Evans, the movie producer who went on to make The Godfather with Francis Ford Coppola, was a regular partner of mine. In one match, Spencer almost took his head off with a vicious overhead. He was pretty annoyed by the aggressive tactics and started complaining that Spencer and I were colluding with each other. Now really, do you think I would ever do that? He claims to have played over 40 matches with me as his partner and never won a set. We are still friends today, and he’ll never let me live that down.

With Spencer and Dino’s connections around town, we didn’t have any trouble spending our weekends in the hottest bars and restaurants in LA. The Daisy Club, where my friend George was the bartender, was one of my favorites. George was a champion surfer—no wave was too big for him—but tennis was his real passion. He also happened to mix the best whiskey sours in town. It was during one of those nights out that I first met Frank Sinatra. By then, Spencer and I were 18 and having dinner with a girl we knew from high school who worked for Eileen Ford, then the top modeling agency in the world. Mr. Sinatra was at a table across from us and he came over to talk to Spencer.

“Hey, you’re Pancho’s son, right? You guys want to see a show? Settle up and follow me.”

Mr. Sinatra took us next door to a studio where we watched as he recorded three songs for the upcoming Jerry Lewis telethon. It was just the Chairman of the Board, the sound engineers, and us. People would pay a fortune to be in the room when Sinatra sang, and here we were, a couple of kids, having a once-in-a-lifetime show for free.

Pancho once told me a story about Jack Kramer, who had been the world’s best tennis player in his day and who would go on to found the players’ union. Jack thought Pancho was crazy when he told him I was going to be better than Stan Smith. This was the age of tall players—Smith was 6'4", Dick Stockton 6'2", Brian Gottfried and Erik Van Dillen were both 6'0". I was 5'9", skinny, and had a double-handed backhand. What chance did I have? Jack thought. Erik Van Dillen even refused to play a match with me once at the LA Tennis Club, saying, “Why? He’s too small.” Pancho’s reply was typical. “Don’t give me that shit. He’s going to kick your ass.”

That was the kind of thing Pancho saw as his challenge—and mine. He told me not to worry about what anyone else said. “They’re tall, Jimbo”—it was OK if Pancho called me that—“but they move like turtles with broken legs. Listen to me, and I can help you be a champion. You have a choice: You fight to be the best, or you settle for being one of many with all the others.” That was a big moment for me. It was then that I fully realized I wasn’t in California just to escape East St. Louis. With Pancho’s help, I was there to be number one.

I worked hard with Pancho, but it wasn’t any less fun. He’d run Spencer and me all over the court from corner to corner. We’d be exhausted and he’d be laughing his ass off because he knew we never wanted him to think we weren’t up to the task, no matter what he threw at us.

“Boys, you’ve got to understand this is what you’re going to face when you take on the best.” There was always a purpose.

Pancho’s methods were similar to Mom’s. If I made a mistake in pract

ice, like not staying low enough on a backhand down the line, he would stop the session, explain the problem, and show me exactly what I’d been doing wrong and how to fix it. If I would miss a backhand down the line, he would actually come onto the court and show me how to do it. I was a visual learner, so being able to see how it was done correctly was important for me. Pancho didn’t want bad habits creeping into my game, like not moving my feet properly or not getting my racquet back soon enough. If I messed up in a match, he would wait a day or two before telling me what the problem was. I remember a match against Roy Emerson at the LA Tennis Club during which I didn’t take the ball early enough and move forward at the right time. Pancho said nothing for 24 hours. Then he took me back on the court and demonstrated how I should have played Emerson.

He was, and remains, my mentor, along with Mom. Without the two of them, I would never have become a champion. What Pancho taught me during those years at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club would fill 10 volumes if I tried to compile the lessons. But it really comes down to three words: confidence, aggression, and strategy.

When I started up with Pancho, my groundstrokes were already in place. Running down every ball came naturally, and my concentration and footwork were probably as good as anyone’s. Thanks to Pop’s training I could reach the ball quickly, which gave me extra seconds to decide where I was going to hit my return. Pancho’s training added a layer of sophistication to my game.

His first step was to make me more aggressive. I had always been a traditional baseliner, keeping the ball in play and slugging it out in long rallies. Pancho taught me to put my opponents on their heels, forcing them to place shots inside my service line.

Pancho called that area of the court the “winning zone.” “If you have the ball there,” he would say, “you control the point, you have options—short, deep, volley.” Pancho showed me how to put my opponent in a defensive situation and bury him. My killer instinct took over as my confidence grew.

“Coach,” I used to say to Pancho before a match, “I’m going to make that guy walk bowlegged like you.” He loved that.

If I took a chance and missed, that was OK, because I knew I’d get better. I had no fear, especially on the big points, the ones that make a difference in the match. You can be in the best shape of your life, hitting the ball great, but if you can’t come through when it counts, you ain’t walking away with the trophy. That’s where Tiger Juices come in.

A huge part of my tennis education with Pancho was on the mental side of the game. It’s a given that every professional can hit the ball well, but the difference between the 100th best player in the world and the number one is minuscule, and it isn’t found on the court. It’s in your head and guts. They didn’t call Pancho “Sneaky” for nothing. He was brilliant at messing with your head. He would do the opposite of what you expected. If you moved in to cover a drop shot, he’d lob you; if you stayed back to force a rally, he’d come up with an angled volley. Pancho always knew the right shot to play, because he used the score to his advantage.

We used to sit at one of the tables in the club snack bar and Pancho would draw diagrams on cocktail napkins to illustrate how to play key points. The strategy would depend on the match situation. If you’re ahead, you do one thing; if you’re behind, you do something else. At 30-15, you can force the next point, move in quickly on your return, and put your opponent under immediate pressure. If you’re down 30-40, you have to nail your first serve, and make sure you pull your opponent out of position, then keep him pinned back with deep balls to prevent him from attacking. It sounds simple, yet making it happen is anything but.

Before my matches, Pancho would pull out those cocktail napkins again to show me the strengths and weaknesses of my opponent and how I could combat their particular approach to the game. He would create these scenarios, like it’s 30-30 on the other guy’s second serve, then explain how the guy would probably play the point. When these moments came up in a real match, I could anticipate them and get the edge. Or he would notice certain traits, like how to tell from the angle of my opponent’s racquet if his shot was going to be short. Or the way an opponent tossed the ball up on his serve might indicate whether it was coming down the center or out wide.

Pancho didn’t have to keep hammering any of this into my head. I ate it up. I devoured every word. Tennis isn’t rocket science, but Pancho simplified things in a way that made perfect sense. Because I trusted him, I wasn’t afraid to incorporate his instructions into matches, no matter how high the stakes. I never, ever thought I had reached the point where I knew everything about the game. I worked hard every day. There was nothing else in the world I would rather have been doing.

All the top juniors in Southern California found their way to the Beverly Hills Tennis Club. The competition back then was the best in the country, and not only between young players. On any given day you might see Arthur Ashe or Stan Smith hitting balls on the back courts. The world’s best players would come to us, or we’d find them at UCLA or USC.

Almost every guy I played would have a different weapon, a different skill—big serve, baseline, power, net game, height, speed, topspin, you name it—and I faced these variations on a regular basis. Nothing I came across in the world’s major tournaments ever surprised me.

Tennis never became a drag, because we never played in the same place two days in a row. If we weren’t at the Beverly Hills Tennis Club or over at one of the LA colleges, we might be up in Bel Air playing at Bobby Kreiss’s court, in the garden behind his house. Spencer and I would sit around having a Coke, watching Bobby’s father put his three sons through their paces, and after a while we’d join in. We were all friends, so there was more to practice than just the tennis; it was a chance to be with our buddies while we worked.

Some of Pancho’s pals—like Bobby Riggs, Pancho Gonzales, Charlie Pasarell, Rod Laver, Ken Rosewall, and Roy Emerson—would stop in to see him when they were passing through Los Angeles. Any time these guys were hanging around and talking, Spencer and I would be in the corner, soaking up as much information as possible. We never spoke ourselves; we just listened. At the end of the day, Gonzales might say to me, “Come on, kid, and hit some balls with me.” Me? Play with Pancho Gonzales? Hell, yes!

Gonzales wasn’t an easy guy to get to know—he could be moody and difficult—but after a while he seemed to accept me, and I loved watching him play. For a big man he was surprisingly elegant, moving about the court with agility and finesse. And he could do things with his racquet that I’d never seen before, particularly when he was at net, where he angled his volleys with deadly precision. I learned a lot, not just by studying his game but by seeing the kind of killer instinct he brought to every match. “The great champions were always vicious competitors,” I remember him saying. “You never lose respect for a man who is a vicious competitor, and you never hate a man you respect.” That seemed a pretty good code to live by.

One afternoon, I’d been watching Gonzales play for about an hour. After every couple of games, he walked to the back of the court and beat his Spalding Smasher against the concrete wall.

“Excuse me, Mr. Gonzales, but with all due respect, what the hell are you doing?”

“Kid, look here. The top of my racquet is out of shape now. I want to see how the ball reacts when I hit it off the strings there. Maybe I can find a new shot. I don’t know, but I’m going to try and figure it out.”

“See this tape around the rim? It’s lead,” he continued. “It makes the racquet heavier so I can let the racquet do some of the work. Here, take some and try it yourself.”

That proved to be a huge part of my success with the T2000, because it added the extra weight that I needed to be able to keep that racquet under control. If I was tired, I would take the lead tape off. If I was feeling good, I would add a little more for increased power.

During my first year in Beverly Hills, I went with Spencer, Dino, and the two Panchos to Phoenix for a pro-am tournament. We flew the

re on a plane owned by Kirk Kerkorian, a businessman who helped make Las Vegas into what it is today. No one loved playing or being around tennis more than Mr. Kerkorian. I was buzzing before we even got to the airport. Private jet?! Oh, yeah.

I played Gonzales in a singles exhibition. It was sweltering in Phoenix, and during one of the changeovers Pancho paused to give me a piece of advice.

“Kid, I want you to drink some orange juice. It’s hot and you need the fluid.”

I wasn’t really an OJ guy, but this was Pancho Gonzales, so I said, “OK.”

“Just take a couple of sips,” he warned me. “Too much and you’ll cramp.”

At the next changeover, he told me to do the same thing again, and the next, and pretty soon I started to stagger. He had been giving me screwdrivers in that heat! You know, vodka and orange juice. You’d think at 16 years old I would have noticed. I could barely hit a ball and the two Panchos couldn’t stop laughing. They taught me a good lesson: Tennis and alcohol don’t mix—not on the court, anyway.

At the time I saw it as a sign that I had been accepted, but, more than that, the two Panchos were showing me that it was OK to have some fun and to entertain the fans while you were playing.

At some point during that trip I called the landlord of my apartment to ask him to check up on my car. The Corvette had become like a pet to me, since I didn’t have my dog.

“Yeah, about your car,” the landlord said, “your friend came and picked it up. I gave him the spare keys you left. Next time you probably should tell me things like that before you leave.”

What?! “I didn’t have someone come to take my car,” I told him. “What the hell?”

“Well, he knew all about you and he had a set of keys to your apartment. He said you must’ve forgotten to say something about it.”

The Outsider: A Memoir

The Outsider: A Memoir